The history of a thing, in general, is the succession of forces which take possession of it and the co-existence of the forces which struggle for possession. The same object, the same phenomenon, change sense depending on the force which appropriate it.

- Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche & Philosophy

What is Tiananmen Square (as it stands today)? How can we begin to understand it as a manifestation of the cultural and political reality of contemporary China? We might start by saying that it is oceanic. It defined by/in its excessiveness, its openness and its indeterminacy; it is a receptacle for the mobilization of the body-politic. It is composed in the meanderings of the crowd and the systems, overt and covert, that control and orchestrate the behavior of this crowd. It is the site of hyper-surveillance. It is un-centered even as it forms the symbolic center of the nation. It is the seat of power and the diagram of that power, replicated ad infinitum throughout the urban spaces of the country.

The square is subject to a variety of co-existent and at times competing forces. These forces, emanating from symbolic and infrastructural elements placed in and around the square, are both active and reactive, stabilizing and destabilizing, consistent with tradition and a radical departure from that tradition. These forces are encapsulated in the diagram of the site, they define that diagram. In the same sense that the Gothic Cathedral served as a microcosm of the ontological structure of medieval Europe, Tiananmen square operates as a microcosm of the Chinese super-structural reality. The political and cultural imperative of the square and the way in which it represents and broadcasts the authority of that symbolism is dependent on its capacity to operate as a genuine and recognizable microcosm.

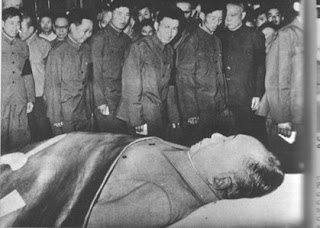

Tiananmen square is also the site of the body of Mao Zedong, a phenomenon in itself, replete with its own history of successive possessions and commiserate conformations as a sense-event. Again, it serves both as a stabilizing and destabilizing force in the cultural ecology. The decision to preserve Mao's body and display it in the square must be seen in terms of the Cultural Revolution and the power struggle that followed his death in 1976. Following a series of carefully ritualized events of mourning – and contrary to his apparent wishes to be cremated – Mao's successor, Hua Guofeng announced the decision to construct a monument to house and display Mao's preserved body. This announcement came eighteen days after Mao's death and just two days after Hua's secrete arrest of the radical leftist Gang of Four, primary rivals in the struggle for control of the CCP. Thought by many at the time as politically naive, an empty figurehead subject to the manipulations of various factions of Party leadership, Hua was able to outmaneuver the Gang of Four (and for a time the moderate-reformists led by Deng Xiaoping) by co-opting the symbolic mantle of authority provided by the iconification of Chairman Mao. This move was exemplified by the "Two-Whatevers Campaign" formulating the policy of the Chinese government in the terms of the following statements: "We will resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made, and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave." Hua understood the direct and perhaps indelible association between Mao and the apparatus of state power, that there was no state without Mao. The act of preservation was a symbolic gesture with a far greater reach, implicating and facilitating a systemic concretization of the Party institutions in transition. The state was stabilized in the enduring image of Mao, on display for all to see. This had very specific effects on the diagram of Tiananmen square. Quite contrary to Mao's ideology of the perpetual revolution and, it must be imagined, the overt intentions of the designers, "the building interrupted the continuities of the square. Symbolically, the unending flow of temporal change...was blocked and then truncated. The mausoleum seemed to seal off history rather than enlarge it." In this sense, the monument became a stabilizing force, fixing the agency of the square in history.

Perhaps, however, we should look at preservation of Mao's body in a different light, held apart from the from the impact of the memorial architecture to the square. In a fascinating discussion, A.P. Cheater explores the symbolic implications of the body and the memorial in the context of traditional burial rites, customs, superstitions and propriety, in other words the cultural imaginative of death. In particular, he questions the anthropological narrative implied in Mao's edifice: "Why...is Mao's final resting place...referred to as a 'memorial hall' [jiniantang]? Has it perhaps to do with the ambiguity, in Chinese funerary custom, of permanent preservation of the flesh, as opposed to the bones? Is Mao dead, or alive, or ambiguously neither – the perfect joker defying normal classification, Monkey, forever? In the old taboo of words, has death – at least for Mao – become almost anti-socialist" Who is this 'joker', this 'Monkey, forever'? Perhaps, rather than fixing the iconography of Mao, the preservation had in the long term the opposite effect, enacting a symbolic castration of the organ of state power (Mao) from the body of that power (the state and the CCP), severing the excessive formation of this organ from the fixation of the apparatus of the political and cultural narrative. This freed the state to evolve beyond Mao (as evidenced by the rapid supplantment of Hua Guofeng by Deng Xiaoping and the economic reformists from 1978 to 1982). But perhaps more importantly, it freed the iconography of Mao from its corporeal bind, allowing it to virtualize, multiply and proliferate. Rather than symbolizing a fixed edifice, Mao's body, in its emptiness, suggests an explosive multiplicity related, ironically, to the ontology of perpetual revolution on the one hand, and a rampant capitalism on the other. As one visitor to the memorial commented: "I used to think of Mao as a god. Now I see him as a man just like any other." He is among us, he is with us, he us.

It is worth exploring further this notion of symbolic castration and its relation to the Sense-Event. Slavoj Zizek frames this in his conflation of Psychoanalytic and Deleuzian conceptualization of the production of autonomous symbolic meaning: "'Symbolic Castration' is an answer to the question: how are we to conceive the passage from bodily depth to surface event...how are we to articulate the 'materialist' genesis of Sense":

The universe of Sense qua 'autonomous' forms a vicious circle. We are always-already part of it, since the moment we assume towards it the attitude of external distance and turn our gaze from the effect to its cause, we lose the effect. The fundamental problem of dialectical materialism is therefore: how does this circle of Sense, allowing for no externality, emerge? How can the immixture of bodily drives give rise to 'neutral' thought, that is, to the symbolic field that is 'free' in the precise sense of not being bound by the economy of bodily drives, of not functioning as a prolongation of the drive's striving for satisfaction? The Freudian hypothesis is: through the inherent impasse of sexuality...Sexuality is the only drive that is, itself, hindered and perverted, being simultaneously insufficient and excessive (with excess as the form of appearance of lack)...[The] capacity of sexuality to overflow the entire field of human experience so that everything, from eating to excretion, from beating up our fellow man (or getting beat up by him) to the exercise of power, can acquire sexual connotation – is not the sign of its preponderance. Rather, it is the sign of a certain structural faultiness: sexuality strives outward and overflows the adjoining domains precisely because it cannot find satisfaction in itself, because it never attains its goal...

How, then, do we pass from the state in which "the meaning of everything is sexual," in which sexuality functions as the universal signified, to the surface of the neutral-desexualized literal SENSE? [capitalization added] The desexualization of the signified occurs when the very element that coordinated (or failed to coordinate) the universal sexual meaning (i.e. the phallus) is reduced to a signifier. The phallus is the 'organ of desexualization' precisely in its capacity as a signifier without signified. It is the operator of the evacuation of sexual meaning (i.e., of the reduction of sexuality qua signified content to an empty signifier). In short, the phallus designates the following paradox: sexuality can universalize itself only by way of desexualization, only by undergoing a kind of transubstantiation in which it changes into a supplement-connotation of the neutral-asexual literal sense.

One can see how Mao (and the body of Mao) function both prior to and through this transubstantiation, as the "coordinator of the universal (sexual) meaning" and the "operator of the evacuation" (of that sexual meaning), that Mao is phallus par excellence.

1 comment:

Hey jordan,

I put a link to your blog on mine

I hope you does'nt mind!

m.

www.styleisdead.blogspot.com

Post a Comment